Understanding Scalability in System Design

Ever wonder why some websites effortlessly handle millions of users while others buckle under the slightest surge? It all boils down to something called scalability. Just because a system works perfectly today doesn’t guarantee it’ll hum along smoothly in the future. As user bases grow and demand increases, systems can degrade. Think about going from 1,000 concurrent users to a whopping 10,000 – that’s a massive jump!

Scalability is all about a system’s ability to cope with increased load. In system design, we constantly ask: If our system explodes in popularity, what are our options? How do we add more computing power to keep things running smoothly?

Let’s dive into the fascinating world of scalability!

First Things First: Describing the Load

Before we can even think about growth, we need to understand our current situation. This means accurately describing the current load on our system. We use load parameters – numbers that tell us what kind of traffic our system is handling.

These parameters vary depending on the system’s architecture. For instance:

- Number of requests per second: How many times users are asking our system to do something. For a social media feed, this could be the number of times users scroll and new posts are fetched.

- Read-write ratio: How many times users are just looking at data (reads) versus creating or changing data (writes). Social media giants like Twitter and Instagram often have a very high read ratio, as millions of people view posts, but only a fraction are actively posting.

- Hit rate on a cache: If we’re using a cache (a temporary storage for frequently accessed data), how often are we successfully finding the data there? A high hit rate means our cache is working efficiently and reducing the load on our main database.

- Active users: The number of users currently interacting with the system.

The bottleneck (the slowest part of the system that holds everything else back) is often dominated by just a couple of these extreme cases – like those read-heavy operations in social media.

What Happens When the Load Increases? Describing Performance

Once we’ve got a clear picture of our current load, we can start investigating how our system behaves under pressure. There are two main ways to look at this:

- Fixed Resources, Increased Load: What happens to our system’s performance if we throw more users at it but don’t add any extra CPU, memory, or network bandwidth? Does it slow down? Crash?

- Increased Load, Constant Performance: How much more CPU, memory, or network bandwidth do we need to add to keep the system performing just as well even with more users?

To answer these questions, we rely on “performance metrics”:

- Throughput: This tells us how many tasks or jobs our system can complete per second. For a batch processing system like Hadoop (which processes large datasets offline), throughput is key – it’s about how much data it can crunch in a given time.

- Response Time: This is what the client (the user) actually sees: the time between sending a request and getting a reply. Imagine clicking a link on a website – the response time is how long it takes for the new page to load.

- Median Response Time is often a better metric than average because it’s less affected by a few very slow requests.

- We also look at percentiles, like the 80th or 99th percentile. This helps us spot outliers – those unusually slow requests and how often they happen. These high-percentile response times are often called tail latency.

- Latency: This is the time a request spends waiting to be handled. Think of it like being in a queue at the supermarket. You’re waiting your turn, even if the cashier is working fast.

Latency vs. Response Time: What’s the Difference?

It’s a common point of confusion!

- Response time is the total time the client experiences. It includes everything: the actual time the server spends processing the request, any delays in the network, and any time spent waiting in a queue.

- Latency is specifically the waiting time for a request before it even starts being processed.

We can think of response time not as a single number, but as a distribution of values. Some requests will be super fast, others a bit slower, and a few might be quite slow.

The Dreaded Queueing Delay

Servers have limits. They can only handle a certain number of tasks at the same time (think of a limited number of CPU cores). So, if many requests come in at once, some of them have to wait in a queue. Sometimes, even a small number of very slow requests can hold up everything behind them. This is like one very slow person at the front of a line, causing everyone else to wait. This effect is also known as head-of-line blocking.

Tail Latency Amplification: A Chain Reaction of Slowness

Imagine a single user request needs to talk to multiple different services in the background to complete its task. Even if we send out those requests in parallel, the user still has to wait for the slowest one to finish before they get their response.

This means that even if only a tiny percentage of those backend calls are slow, the chance of encountering a slow call goes way up if a single user request needs to make many backend calls. The end result? A larger percentage of end-user requests end up being slow. This phenomenon is called tail latency amplification. It’s like a chain is only as strong as its weakest link.

When Every Request is a New Beginning: Stateless Systems

A stateless system is designed so that each request contains all the necessary information for the server to fulfill it, without needing to remember anything from previous interactions.

Think of it like this: If you go to a vending machine, each time you put in money and make a selection, it’s a completely new transaction. The machine doesn’t remember what you bought last time. Similarly, a stateless system doesn’t store any session information about a user between requests. If any state is needed, the client (your web browser, for example) usually holds onto it.

Stateless systems are generally easier to scale because any server can handle any request, making it simple to distribute the load.

How to Cope with the Load: Scaling Strategies

Once we have a clear picture of our system’s load and performance, we can start strategizing about scalability – how to maintain good performance even when our load parameters skyrocket.

Here are the two main approaches:

-

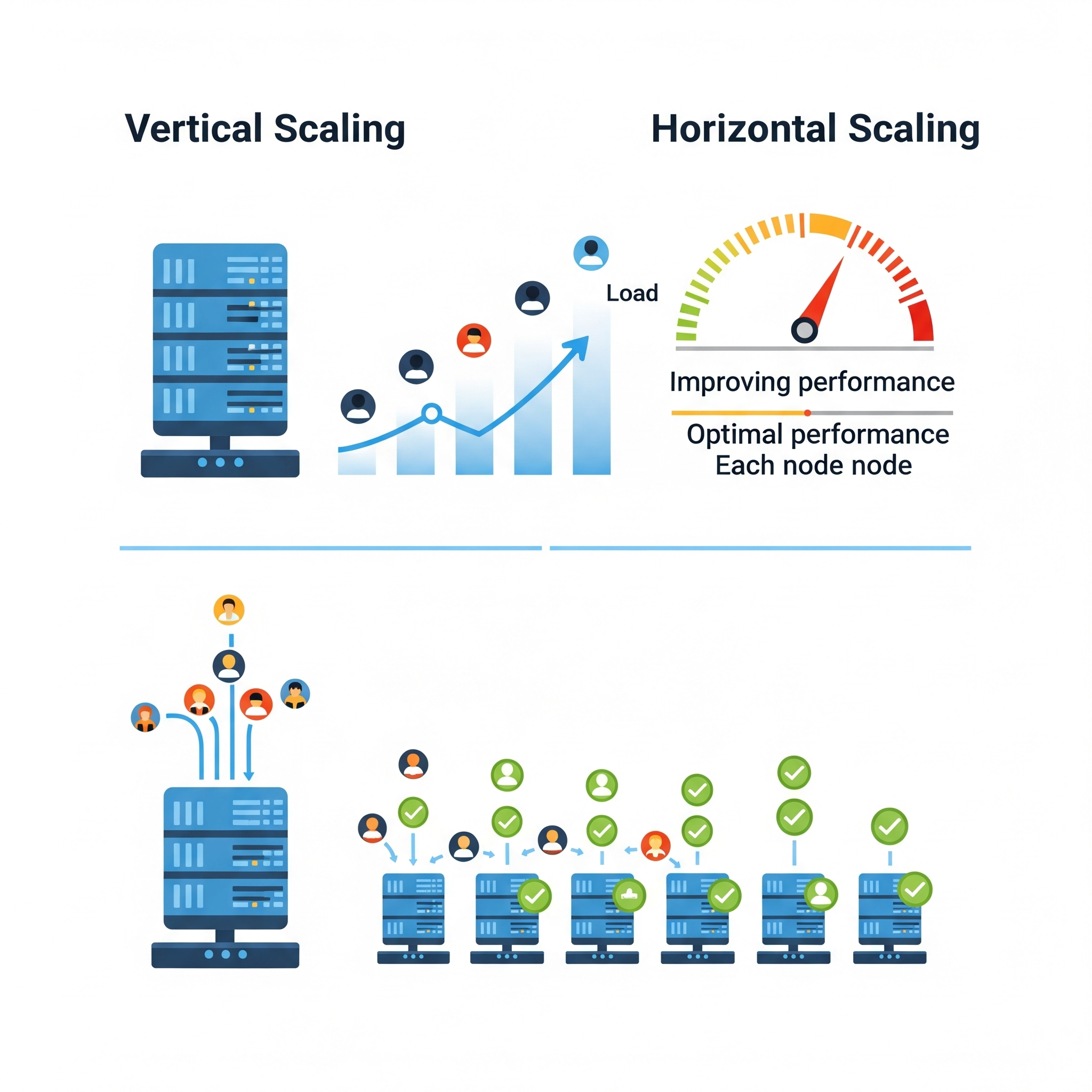

Scaling Up (Vertical Scaling): This means moving to a more powerful single machine. Imagine upgrading your home computer with more RAM, a faster CPU, or a bigger hard drive. It’s often the simplest solution initially, as you don’t have to deal with the complexities of multiple machines. However, large, powerful machines can get incredibly expensive, and there’s always an upper limit to how much you can beef up a single box.

-

Scaling Out (Horizontal Scaling): This involves distributing the load across multiple, smaller machines. It’s also known as a shared-nothing architecture because each machine ideally operates independently. Think of it as adding more checkout counters at a busy supermarket instead of just making one counter super fast. While more complex to set up, horizontal scaling offers much greater flexibility and cost-effectiveness in the long run.

Elastic Systems: The Ultimate Flexibility

An elastic system takes horizontal scaling a step further. It’s a system that can automatically add or remove computing resources (like virtual servers) based on whether the load increases or decreases. This is super helpful when the load is unpredictable, like during a flash sale or a viral event. Cloud providers like AWS and Google Cloud make this much easier to achieve.

The Big Takeaway: No One-Size-Fits-All Solution

Designing a truly scalable architecture is highly specific to the individual system or application’s needs. There’s no magical one-size-fits-all solution. The core problem might be:

- Too many read operations on your database.

- A processing step that takes too long.

- The sheer complexity or size of your data.

Scaling a system is all about pinpointing the specific bottlenecks and dealing with those problems effectively within that particular system. It’s a continuous process of monitoring, analyzing, and adapting your architecture to meet ever-evolving demands.

Conclusion

Understanding scalability isn’t just for system architects; it’s a fundamental concept for anyone involved in building reliable and performant software. By carefully describing the load, understanding performance metrics, and strategically applying vertical or horizontal scaling techniques, we can build systems that not only run reliably today but also confidently handle the challenges of tomorrow’s growth. The future of your system depends on it!